Behavior Information updated February 25, 2021

-Tips for new dog or pup in the home

-Aggressive dog issues / recommendations / stances

-Great behavior article

-Separation anxiety tips,

-Aggressive dog issues / recommendations / stances

-Great behavior article

-Separation anxiety tips,

Behavior Sites |

Anxiety/Storm/Noise Phobia Products

|

Reactive Dogs

|

|

Decompression Tips for your Dog

-Body Language Info -Separation Anxiety Management -Dog Training & Behavior -Video on teaching handling -WonderPuppy.net Can We Help You Keep Your Pet ? -UncleMatty.com -Clicker Training -Dr Karen Pryor, Housebreaking |

Storm Phobia Help

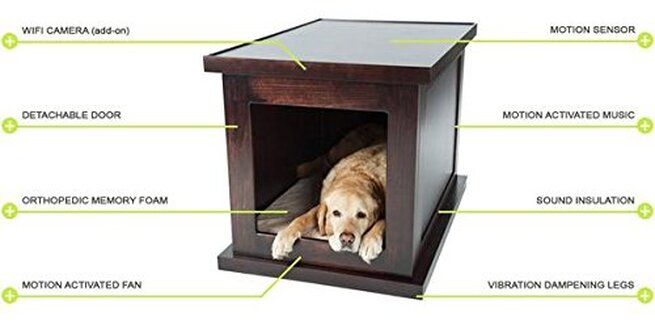

This crate is no longer available for purchase, but you can create your own. Search, "soundproofing dog crates".

Behavior Help Lines &

|

Behavior Videos, Info |

|

-Pet Behavior Partners a great option for training and calming medications that can only be prescribed by a veterinarian

* Delighted Dog Training * Franklin County Dog Shelter 614-525-5449 * Calm Canines Training [email protected] 614-310-5154 * Vilma Briggs [email protected] 614-205-9429 * Sheila Ferguson [email protected] 614-267-7254 * Sharon Smith [email protected] 614-778-0431 * ASPCA 212-876-7700 x 4357 * San Francisco SPCA 415-554-3075 * Univ of PA Sch of Vet Med Behavior 215-898-3347 * Tufts Univ Sch Med Behavior (fee) 508-839-7934 |

Crate Training, make your dog love his/her crate

Video on training for calmness (above link says error, but video starts playing in 15 seconds) Capturing Calm Article |

Interactive ToysInteractive Toys

The Everlasting Treat Ball Kongs Bopperoo Jack Busy Buddy Kibble Nibble Hol-ee Mol-ee Nylabone Double Action Chew Tuffy's Ultimate Rumble Rind Busy Buddy Squirrel Dude ActiveDogToys.com They categorize toys as follows; Fetch Toys, Bubble Toys, Outdoor Toys, Chew Toys and Healthy Treats |

Housebreaking Aids |

Transition Tips for a New Dog or Puppy in the Home

These tips apply to any dog/puppy entering a new environment

Get Pet Acoustics.com for your fearful dog, dogs afraid of fireworks or thunder: Scientifically proven to relax dogs, tv & radio are counter productive, white noise is better but Pet Acoustics is best.

Building Relationships with Fearful Dogs from Best Friends in Utah

These tips were compiled from our foster homes who have had many breeds, temperaments, ages, backgrounds of dogs and pups.

Foster homes have become familiar with how to help dogs in transition adjust quickly and most peacefully for both the dog and humans to their new homes.

---- Adjustment Time It can take a few days for a dog to adjust to a new home. Patience & management are key.

-Upon arrival, don’t immediately allow the dog free-roam or up on furniture. It’s best for you to provide the dog 100%

supervision at first. The dog doesn’t have the chance to get into unwanted habits (chewing, accidents, digging)

-Crate your new dog or leash them to you in the house, gradually allowing them more freedom, keeping up the supervision.

If your new dog “makes a mistake” and you weren’t watching, that was really your mistake, not the dog.

-Dogs benefit from schedules/routines, it’s critical to be consistent. Dogs that know what to expect next are calmer and more

comfortable. Keep the routines on weekends. Give your new dog successful situations, if they know sit, do it often & praise with treats

and physical touch. A firm “NO” is the best correction with quick re-direction to show them what behavior you want.

---- Leadership Good dog pack leaders are confident, reasonable, gentle, consistent and obvious to all in the house, alpha dog of the pack.

They don’t need to use force to be in control. For your dog Nothing in Life Is Free! Dogs need direction. You control all resources (meals, treats, attention, praise, walks, furniture, toys) Don’t free feed. Feed twice/day. Ask your dog to “sit” before giving food. They have to

earn their food! Young dogs & new dogs esp. shouldn’t sleep on your bed or be on furniture. Move valuables out of reach. Provide toys one

at a time, always ask for a “sit” first. Don’t give in to needy or pushy behavior. Ignore dog until they are calmer. Turn your back, look away, walk away etc. Always try to be aware of what you are rewarding. When your dog is showing behavior you like, good leaders are lavish & generous with their rewards and praise. Dogs need to know what’s expected of them. Good leaders know their dog’s needs and provide for them. Call your dog by their name from another room. They love hearing their name & come like crazy because someone wants them.

----Names Don’t name a dog a name that ends in “o” like Bo, Joe, Mo. These names sound too much like what most people us to correct with, “NO”

Two-syllable names are really good since most commands are one syllable

---- Crate your dog Done correctly, there is no negative aspect to crate training your dog. It keeps your house safe & the dog safe. It

keeps your dog from developing bad behavior habits. The crate should be a place of comfort and safety for them to call their own. If

puppy doesn’t destroy it, put comfy bedding/blankets in. Feed meals in the crate, give treats for going in. Have a special “Crate only” toy/chew. If your pup fusses – ignore them. Avoid letting a noisy fussing dog out of the crate, wait until they are quiet for several minutes, praise them and let them out. Especially in the beginning, keep crate times to short periods. As you are sure the dog is comfortable,

gradually increase the time and vary it. Sometimes just crate your pup for 10 mins while you’re home.

Never use the crate as punishment.

Never crate your dog in anger. Always treat your dog for going into the crate.

---- Sleeping Area Have your new dog sleep on the floor in your bedroom (or in crate, leash to bed frame or nightstand, this will help them

settle down) Sleeping in the room with you gives them much needed companionship even though you are sleeping.

----Multiple Dog Dog Homes put a rubber band around the tags of the dogs in the home to prevent excitability

---- Home Alone It’s important to get the dog use to your leaving from the start. Make sure that the first few times you leave are

low stress for your dog. Leave him when he’s tired, leave him with something yummy to occupy him. Keep departures & arrivals low-key. Ignore your dog 10mins (no talking / touching / eye contact!) before walking out and after returning. Wait until the pup is calm before you acknowledge them. Ask them to “Sit” – when they do calmly pet and say hi -Keep absences short at first and vary the length of time you are gone. Start at 10 mins and build from there. He will soon get the idea that you always come back and there’s no need to worry.

---- White Noise Use a fan or white noise machine to drown out the kids yelling on the street, the delivery man leaving something at your house.

Don't use a radio or tv as they change pitch and volume. White noise can make a tremendous difference in calming a dog down while you are not home.

---- Housetraining Be patient. Even house-trained adult dogs may have accidents/relapses while they are adjusting to a new home

1 Pick a spot outside for bathroom area and use it consistently 2 Take your dog out after they awake, eat, have a big play

inside the house 3 If you see your dog sniffing/ circling in the house, take him out immediately 4 Praise/reward him with a treat

when he relieves himself outdoors 5 Never yell/punish your dog for a potty accident in the house, this will make things worse

6 Clean accidents with enzymatic cleaners or 50/50 vinegar/water to prevent them from being drawn back to that area

---- Chewing/Digging Make sure that you have safe/suitable things for your dog to chew on. Nylabones/Kongs etc. If pup starts to chew on something they aren’t supposed to, redirect them to something they are and then give them lots of praise & a treat. Avoid chasing after dogs that have “stolen” something (unless it’s dangerous to them). Grab some treats and pretend to eat them, your dog will soon realize they can’t make you play chase. Exchange a treat for the stolen object and praise your pup! Dogs don’t know the difference between a rawhide chew

and a leather shoe, keep shoes out of their reach. Place dogs feces in areas they are digging to discourage them from continuing.

---- Take Walks/Play Games A tired dog is a good dog! Dogs need both physical exercise and mental stimulation. A good exercise program

will make your dog a more relaxed and enjoyable companion. A short walk, twice a day is the minimum. If you are pinched for time, even a

walk to the mailbox will be the highlight of their day. Don’t leave dogs unattended in your backyard. They could annoy neighbors, develop

bad habits or be stolen. Play games with your dog, throw balls outside. Roll them inside. Play hide and seek. Hide toys/treats in the room

and encourage/help the dog to find them with you.

---- Shy dogs need a confidence boost –teach them sit & have them do it often –go on many walks -hand feed dry dog food

-Encourage eye contact then as they do give treats

-make smooching noises and say their name often, when they look at you reward them

-Never raise your voice to these dogs, it makes them more insecure

–don’t baby your dog when they are nervous, it’s natural to do this, but telling them “It’s ok” to be nervous

-be upbeat & confident

-use your happy voice, and then distract them from whatever is making them nervous

-get them used to things that scare them but don’t force them into situations they can’t handle

-use lots of food rewards to build positive associations with things that scare them

-get them used to noises by clapping quietly when they are looking, reward with praise/treats, over time clap louder & while they are not looking, this will help them get used to sudden noises,

-motion with your fingers all waving at the same time to come to you at the same time saying come, this gives an audible as well as visual cue to come to you

-Take your foster on many car rides so they will become comfortable with transport

-Give your foster a toy or a blanket; let them take the toy to their new home so they have something familiar

-“puppy-proof” your house, put electrical cords out of reach, place garbage can under sink

-using the call, “Fluffy Come” to teach the dog to come and you can easily pass this command to his/her permanent guardian-Touch your dog often, this releases endorphins and helps to relax, just a few seconds here and there can make a big difference

Please add your tips & forward to us. [email protected]

Building Relationships with Fearful Dogs from Best Friends in Utah

These tips were compiled from our foster homes who have had many breeds, temperaments, ages, backgrounds of dogs and pups.

Foster homes have become familiar with how to help dogs in transition adjust quickly and most peacefully for both the dog and humans to their new homes.

---- Adjustment Time It can take a few days for a dog to adjust to a new home. Patience & management are key.

-Upon arrival, don’t immediately allow the dog free-roam or up on furniture. It’s best for you to provide the dog 100%

supervision at first. The dog doesn’t have the chance to get into unwanted habits (chewing, accidents, digging)

-Crate your new dog or leash them to you in the house, gradually allowing them more freedom, keeping up the supervision.

If your new dog “makes a mistake” and you weren’t watching, that was really your mistake, not the dog.

-Dogs benefit from schedules/routines, it’s critical to be consistent. Dogs that know what to expect next are calmer and more

comfortable. Keep the routines on weekends. Give your new dog successful situations, if they know sit, do it often & praise with treats

and physical touch. A firm “NO” is the best correction with quick re-direction to show them what behavior you want.

---- Leadership Good dog pack leaders are confident, reasonable, gentle, consistent and obvious to all in the house, alpha dog of the pack.

They don’t need to use force to be in control. For your dog Nothing in Life Is Free! Dogs need direction. You control all resources (meals, treats, attention, praise, walks, furniture, toys) Don’t free feed. Feed twice/day. Ask your dog to “sit” before giving food. They have to

earn their food! Young dogs & new dogs esp. shouldn’t sleep on your bed or be on furniture. Move valuables out of reach. Provide toys one

at a time, always ask for a “sit” first. Don’t give in to needy or pushy behavior. Ignore dog until they are calmer. Turn your back, look away, walk away etc. Always try to be aware of what you are rewarding. When your dog is showing behavior you like, good leaders are lavish & generous with their rewards and praise. Dogs need to know what’s expected of them. Good leaders know their dog’s needs and provide for them. Call your dog by their name from another room. They love hearing their name & come like crazy because someone wants them.

----Names Don’t name a dog a name that ends in “o” like Bo, Joe, Mo. These names sound too much like what most people us to correct with, “NO”

Two-syllable names are really good since most commands are one syllable

---- Crate your dog Done correctly, there is no negative aspect to crate training your dog. It keeps your house safe & the dog safe. It

keeps your dog from developing bad behavior habits. The crate should be a place of comfort and safety for them to call their own. If

puppy doesn’t destroy it, put comfy bedding/blankets in. Feed meals in the crate, give treats for going in. Have a special “Crate only” toy/chew. If your pup fusses – ignore them. Avoid letting a noisy fussing dog out of the crate, wait until they are quiet for several minutes, praise them and let them out. Especially in the beginning, keep crate times to short periods. As you are sure the dog is comfortable,

gradually increase the time and vary it. Sometimes just crate your pup for 10 mins while you’re home.

Never use the crate as punishment.

Never crate your dog in anger. Always treat your dog for going into the crate.

---- Sleeping Area Have your new dog sleep on the floor in your bedroom (or in crate, leash to bed frame or nightstand, this will help them

settle down) Sleeping in the room with you gives them much needed companionship even though you are sleeping.

----Multiple Dog Dog Homes put a rubber band around the tags of the dogs in the home to prevent excitability

---- Home Alone It’s important to get the dog use to your leaving from the start. Make sure that the first few times you leave are

low stress for your dog. Leave him when he’s tired, leave him with something yummy to occupy him. Keep departures & arrivals low-key. Ignore your dog 10mins (no talking / touching / eye contact!) before walking out and after returning. Wait until the pup is calm before you acknowledge them. Ask them to “Sit” – when they do calmly pet and say hi -Keep absences short at first and vary the length of time you are gone. Start at 10 mins and build from there. He will soon get the idea that you always come back and there’s no need to worry.

---- White Noise Use a fan or white noise machine to drown out the kids yelling on the street, the delivery man leaving something at your house.

Don't use a radio or tv as they change pitch and volume. White noise can make a tremendous difference in calming a dog down while you are not home.

---- Housetraining Be patient. Even house-trained adult dogs may have accidents/relapses while they are adjusting to a new home

1 Pick a spot outside for bathroom area and use it consistently 2 Take your dog out after they awake, eat, have a big play

inside the house 3 If you see your dog sniffing/ circling in the house, take him out immediately 4 Praise/reward him with a treat

when he relieves himself outdoors 5 Never yell/punish your dog for a potty accident in the house, this will make things worse

6 Clean accidents with enzymatic cleaners or 50/50 vinegar/water to prevent them from being drawn back to that area

---- Chewing/Digging Make sure that you have safe/suitable things for your dog to chew on. Nylabones/Kongs etc. If pup starts to chew on something they aren’t supposed to, redirect them to something they are and then give them lots of praise & a treat. Avoid chasing after dogs that have “stolen” something (unless it’s dangerous to them). Grab some treats and pretend to eat them, your dog will soon realize they can’t make you play chase. Exchange a treat for the stolen object and praise your pup! Dogs don’t know the difference between a rawhide chew

and a leather shoe, keep shoes out of their reach. Place dogs feces in areas they are digging to discourage them from continuing.

---- Take Walks/Play Games A tired dog is a good dog! Dogs need both physical exercise and mental stimulation. A good exercise program

will make your dog a more relaxed and enjoyable companion. A short walk, twice a day is the minimum. If you are pinched for time, even a

walk to the mailbox will be the highlight of their day. Don’t leave dogs unattended in your backyard. They could annoy neighbors, develop

bad habits or be stolen. Play games with your dog, throw balls outside. Roll them inside. Play hide and seek. Hide toys/treats in the room

and encourage/help the dog to find them with you.

---- Shy dogs need a confidence boost –teach them sit & have them do it often –go on many walks -hand feed dry dog food

-Encourage eye contact then as they do give treats

-make smooching noises and say their name often, when they look at you reward them

-Never raise your voice to these dogs, it makes them more insecure

–don’t baby your dog when they are nervous, it’s natural to do this, but telling them “It’s ok” to be nervous

-be upbeat & confident

-use your happy voice, and then distract them from whatever is making them nervous

-get them used to things that scare them but don’t force them into situations they can’t handle

-use lots of food rewards to build positive associations with things that scare them

-get them used to noises by clapping quietly when they are looking, reward with praise/treats, over time clap louder & while they are not looking, this will help them get used to sudden noises,

-motion with your fingers all waving at the same time to come to you at the same time saying come, this gives an audible as well as visual cue to come to you

-Take your foster on many car rides so they will become comfortable with transport

-Give your foster a toy or a blanket; let them take the toy to their new home so they have something familiar

-“puppy-proof” your house, put electrical cords out of reach, place garbage can under sink

-using the call, “Fluffy Come” to teach the dog to come and you can easily pass this command to his/her permanent guardian-Touch your dog often, this releases endorphins and helps to relax, just a few seconds here and there can make a big difference

Please add your tips & forward to us. [email protected]

Aggression

Generally, the only real option for aggressive dogs is to work out the problem within the household. Placing a dog in another home or shelter doesn't correct the problem - it just relocates it. You don't want to send your dog away without disclosing all issues to the new guardians/shelter/rescue.

You are placing both the people and the dog in a dangerous situation.

Check with your vet

-Have blood work done to determine if there is a deficiency

-check for lyme disease, recent studies attribute unfounded aggression to lyme disease

-check to see if these things are the cause of aggression...

-tooth/ear/joint pain

- flowers like impatiens have caused aggression

A list of behaviorist and trainers can be found under Dog/Cat Info on our front page.

You are placing both the people and the dog in a dangerous situation.

Check with your vet

-Have blood work done to determine if there is a deficiency

-check for lyme disease, recent studies attribute unfounded aggression to lyme disease

-check to see if these things are the cause of aggression...

-tooth/ear/joint pain

- flowers like impatiens have caused aggression

A list of behaviorist and trainers can be found under Dog/Cat Info on our front page.

Dog Postures

|

Playful or Play Bow Posture

The play bow invites others to play. Dogs may use a play bow to communicate that any prior rough behavior was not intended to be threatening. Dogs may also assume this posture if they have done something wrong, to let you know they meant no harm and really just wanted to play. Active Submission Posture A dog displaying active submission behavior is offering signs of submission to a superior dog or person to avoid any additional threats or confrontations. This dog is a bit fearful and hopes the superior individual will either retreat or show signs of friendliness. Defensive Threat Posture

Be very concerned about dogs in defensive threat posture. These dogs are showing signs of fear or submission and aggression. Dogs displaying this behavior are afraid and may attack if pushed. This is the posture assumed by fear biters, dogs who bite out of fear. People often read them wrong, thinking they are harmless because of their facial expression show signs of submission. They do not look beyond the facial expression to the rest of the dog's posture to see what he is really communication. Defensive threat is the most dangerous body posture of dogs Aggressive-Dominant or Offensive Threat Posture

This is a very threatening posture communicating confidence and dominance if confronted. Dogs in this posture are preparing to attack and, if pressed, will bite and will fight. Stressed

Signs of stresses in dogs are as following: Shaking or shivering scratching excessive dandruff(exfoliate) excessive shedding dilated pupils excessive blinking loss of appetite diarrhea restlessness use of calming signals sweating through pads of feet frequent or inappropriate urination panting, salivating biting or licking self hiding or trying to leave Passive Submissive

A completely submissive dog is very afraid of a confrontation. He is signaling to the dominant individual absolute surrender assuring that he is of no threat. Some dogs may show complete submission, expect their inguinal (groin) region, as a friendly gesture differing to their owners or their animal friends. |

Do Dogs Think? Owners assume their pet's brain works like their own. That's a big mistake.

Jon Katz, author

Blue, Heather's normally affectionate and obedient Rottweiler, began tearing up the house shortly after Heather went back to work as an accountant after several years at home. The contents of the trash cans were strewn all over the house. A favorite comforter was destroyed. Then Blue began peeing all over Heather's expensive new living room carpet and systematically ripped through cables and electrical wires.

"I know exactly what's going on," Heather told her vet when she called seeking help. "Blue is angry with me for leaving her alone. She's punishing me. She always looks guilty when I come home, so she knows she's been bad. She knows she shouldn't be doing those things." Heather's assessment was typical of many dog owners' diagnoses of behavioral problems. And her vet agreed, suggesting "separation anxiety" and prescribing anti-anxiety medication for Blue. Heather also hired a trainer, who confirmed the diagnosis.

Blue, they concluded, was resentful at her owner's absence and was misbehaving to regain the attention that she'd once monopolized. After all, Blue didn't transgress like this when Heather went out shopping or took in a movie with friends. It must be punitive. Heather's mother even recalled Heather, as a child, throwing tantrums when she went off to work. Heather and Blue had become so close, she joked, that they were acting alike. So Heather shut Blue in the kitchen with a toddler gate, removing countertop food and garbage. Things calmed down. Heather began to relax and gave Blue the run of the house again.

Heather, a friend of a friend, had called me for counsel as well. But since she, her vet, her trainer, and her mother had all reached the same conclusion, and since the rampaging had stopped, I didn't give the situation much thought. A month later, though, Heather was back on the phone: Blue had relapsed. She yowled piteously when confined to the kitchen or basement. Worse, she was showing signs of aggression with people and other dogs and refusing to obey even simple commands that were once routine. On one late-night walk, Blue attacked a terrier walking nearby, opening wounds that needed stitches.

Blue's problems had grown so serious that kennels wouldn't board the dog and the vet wouldn't examine her without a muzzle. Heather was thinking of finding her another home, turning her over to a rescue group, possibly even euthanizing her. "She's out of control," Heather complained, exhausted, angry, and frightened. She sounded betrayed—a dog she'd loved and cared for was turning on her because she went to work. "I caused this by leaving her," Heather confessed, guiltily. But was she supposed to quit her job to stay home with her dog?

This time, Heather got my full attention. I took notes, asked questions, then called a canine behaviorist at Cornell and explained the problem in as much detail as I could. "Everybody says the dog was reacting to her going back to work," I suggested. "Everybody is probably wrong," was his blunt comeback. "It's 'theory of mind.' This is what often happens when humans assume that dogs think the way we do."

His analysis: "Being angry at the human and behaving punitively—that's not a thought sequence even remotely possible, given a dog's brain. The likely scenario is that the dog is simply frightened." When Heather was home, she was there to explain and enforce the rules. With her gone, the dog literally didn't know how to behave. The dog should have been acclimated to a crate or room and confined more, not less, until she got used to her new independence.

Lots of dogs get nervous when they don't know what's expected of them, and when they get anxious, they can also grow restless. Blue hadn't had to occupy time alone before. Dogs can get unnerved by this. They bark, chew, scratch, destroy. Getting yelled at and punished later doesn't help: The dog probably knows it's doing something wrong, but it has no idea what. Since there's nobody around to correct behaviors when the dog is alone, how could the dog know which behavior is the problem? Which action was wrong?

He made sense to me. Dogs are not aware of time, even as a concept, so Blue couldn't know whether she was being left for five minutes or five hours, or how that compared to being left for a movie two weeks earlier. Since she had no conscious notion that Heather's work life had changed, how could she get angry, let alone plot vengeance? The dog was alone more and had more time to fill. The damage was increasing, most likely, because Blue had more time to get into mischief and more opportunities to react to stimulus without correction—not because she was responding to different emotions.

I was familiar with the "theory of mind" notion the behaviorist was referring to. Psychologist David Premack of the University of Pennsylvania talks about it; it's also discussed in Stanley Coren's How Dogs Think. The phrase refers to a belief each of us has about the way others think. Simply, it says that since we are aware and self-conscious, we think others—humans and animals—are, too. There is, of course, enormous difference of opinion about whether this is true.

When I used to leave my border collie Orson alone in the house, uncrated, he learned to open the refrigerator with his nose, remove certain food items, open the plastic container, and consume its contents. Then he'd squirrel away the empty packages. Everyone I told this story made the same assumptions: Orson was a wily devil taunting me for leaving him alone. We actually installed a child lock on the refrigerator door. But what changed his behavior was that I began to crate him when I went out. He has not raided the fridge since. Yet he could easily sneak in and do that while he's uncrated and I'm occupied outdoors or elsewhere in the house. Is he no longer wily? Or is he simply less anxious?

There's no convincing evidence I'm aware of, from any reputable behaviorist or psychologist, that suggests dogs can replicate human thought processes: use language, think in narrative and sequential terms, understand human minds, or share humans' range of emotions. Yet that remains a powerful, pervasive view of dogs, the reason Heather's vet, trainer, and mother all agreed on Blue's motivations. It's almost impossible not to lapse into theory-of-mind reasoning when it comes to our dogs. After all, most of us have no other way in which to grasp another creature's behavior. How can one even begin to imagine what's going on inside a dog's head?

Most of the time, I don't know why my dogs do what they do. They seem aware that I have a way of doing things. They've learned that we don't walk in the street, that I don't distribute food from my plate, that there will be a bone or treat after dinner. But they are creatures of habit and instinct, especially when it comes to food, work, and attention. I often think of them as stuff-pots wedded to ritual, resistant and nervous about change.

I don't believe that dogs act out of spite or that they can plot retribution, though countless dog owners swear otherwise. To punish or deceive requires the perpetrator to understand that his victim or object has a particular point of view and to consciously work to manipulate or thwart it. That requires mental processes dogs don't have. The more I've moved away from interpreting my dogs' behavior as nearly human, the easier it is to train them, and the less guilt and anxiety I feel.

To attribute complex thoughts and plots to their actions unravels the training process. Training and living with a dog requires a different theory: that these are primal, predatory animals driven by instinct. Rather than seeking animalclues to her dog's behavior, Heather imagined herself as the dog. She reasoned that if she, Heather, were suddenly left alone for long periods, abandoned by someone she loved and used to spend a lot of time with, she would feel angry and hurt and might try to get even, not only to punish her companion but to try to persuade him or her to return.

That's attributing a lot of intellectual activity to an animal that can recognize a few dozen words but has none of its own, that reads human emotions but doesn't experience the same ones. Since the Cornell behaviorist made sense to me, I conveyed his analysis: The dog didn't know how to behave with Heather gone. Crating Blue would reduce her anxiety and give her less chance to act up. I persuaded Heather—by now distraught—to buy a large crate. For weeks, she fed the dog in the crate, leaving the door open. Between meals, she left treats and bones inside.

The first time Heather closed the crate door, Blue threw herself against the metal, whining and howling. The same thing happened the second, third, fifth, and dozenth times. But Heather, cautioned that training and retraining often takes weeks and months, persisted. Sometimes she left the treat-filled crate open; other times she closed it.

After several weeks, Blue began to go into the crate willingly and remained there quietly for short, then lengthening periods. Heather walked Blue two or three times daily; when she was gone for more than three or four hours, she hired a dog walker to take her out an additional time and throw a ball. But whenever Heather left the house, she put Blue in the crate and left a nearby radio tuned to a talk network.

This time, Heather got it right, treating Blue as a dog, not a rebellious teenager. Blue improved dramatically, and the improvement continues. Her aggression diminished, then seemed to vanish, although Heather no longer lets her near dogs or children unleashed. It seemed the dog had comprehensible rules to follow, and felt safer.

Blue was liberated from the confusion, anxiety, and responsibility of figuring out what to do with her unsupervised and sudden freedom. Once again there was little tension between the two of them. Heather's house wasn't getting chewed up, and homecomings weren't tense and angry experiences. Yet here was a case, I thought, where seeing canine behavior in human terms nearly cost an animal its life.

Sometimes it does. Harry, a social worker in Los Angeles, wrote me that he had a great rescue dog named Rocket and was happy enough with the experience to adopt a second. Rocket attacked the new dog while Harry was feeding them, then bit a neighborhood kid. "He never forgave me for getting the new dog," Harry explained. "He was so angry with me. I couldn't trust him not to take out his rage on others, so I had him put to sleep."

We will never know, of course, what Rocket could or could not forgive. Rocket probably didn't attack the new dog out of anger at Harry. He was more likely protecting his food or pack position. The creature in the household with the most to lose from a new arrival, he probably simply fought for what he had. Then, once aroused, he was more dangerous. As trainers know, dogs under pressure have two options: fight or flight. Rocket decided to fight and paid for it with his life. Had his owner known more about dogs' true nature, he might have introduced the new dog more gradually, or not at all. And there might be one less bitten child. But this is all a guess. We will never know.

When I face such training problems—and I do, we all do—I try to adopt a Sherlock Holmesian strategy, using logic and determination. We have all sorts of tools at our disposal that dogs don't have. We control every aspect of their lives, from food to shelter to play, so we ought to be able to figure out what's driving the dog and come up with an individually tailored approach that works—and if it doesn't, come up with another one.

Why will Clementine come instantly if she's looking at me, but not if she's sniffing deer droppings? Is it because she's being stubborn or, as many people tell me, going through "adolescence"? Or because, when following her keen predatory instincts, she simply doesn't hear me? Should my response be to tug at her leash or yell? Maybe I should be sure we've established eye contact before I give her a command, or better yet, offer a liver treat as an alternative to whatever's distracting her. But how do I establish eye contact when her nose is buried? Can I cluck or bark? Use a whistle or hoot like an owl?

I've found that coughing, of all things, fascinates her, catches her attention, and makes her head swivel, after which she responds. If you walk with us, you will hear me clearing my throat repeatedly. What can I say? It works. She looks at me, comes to me, gets rewarded.

The reality is, we don't know that much about what dogs think, because they can't tell us. Behaviorists tend to believe that dogs "think" in their own way—in sensory images involving their finely honed instincts. They're not capable of deviousness or spite. They love routine: Nothing seems to make them more comfortable than doing the same thing at the same time in the familiar way, day after day: We snack here, we poop there, we play over here. I am astonished at how little it takes to please them, how simple their lives can be if we don't complicate them.

Dogs' emotional makeup (and their ability to express emotions), their pack instincts to follow and obey, and their intelligence are clearly extremely favorable adaptive traits, since they've allowed Canis lupus familiaris, through its partnership with Homo sapiens, to reach population levels that would have been impossible for it in the wild (compare domestic dog populations with wolf populations.)

What's not so often noticed is that man has corresponding traits that allow him to form a partnership with dogs. His own intelligence and emotions clearly enter into it, but so does his instinctive anthropomorphism (which extends to a great many things, not just animals). We can collaborate with dogs so well, and enjoy them so much, because we cannot help but thinking of them as like ourselves. I couldn't agree more with Katz--I've thought many of the things he says for many years--but that doesn't prevent me from thinking and talking about my dogs exactly like they were my children, my friends, my hunting buddies, etc. Like all dog owners, I feel I can read their minds, but in fact I'm attributing to them thoughts they cannot possibly have.

By fortunate accident, dogs' physiognomy and behavior are close enough to ours that we effortlessly substitute our thoughts for theirs. Yet, inaccurate as this must, it obviously works most of the time. I don't see how we could ever have partnered with dogs but for the closeness of the relationship, and that closeness is partly a consequence of our wildly inaccurate anthropomorphizing.

Blue, Heather's normally affectionate and obedient Rottweiler, began tearing up the house shortly after Heather went back to work as an accountant after several years at home. The contents of the trash cans were strewn all over the house. A favorite comforter was destroyed. Then Blue began peeing all over Heather's expensive new living room carpet and systematically ripped through cables and electrical wires.

"I know exactly what's going on," Heather told her vet when she called seeking help. "Blue is angry with me for leaving her alone. She's punishing me. She always looks guilty when I come home, so she knows she's been bad. She knows she shouldn't be doing those things." Heather's assessment was typical of many dog owners' diagnoses of behavioral problems. And her vet agreed, suggesting "separation anxiety" and prescribing anti-anxiety medication for Blue. Heather also hired a trainer, who confirmed the diagnosis.

Blue, they concluded, was resentful at her owner's absence and was misbehaving to regain the attention that she'd once monopolized. After all, Blue didn't transgress like this when Heather went out shopping or took in a movie with friends. It must be punitive. Heather's mother even recalled Heather, as a child, throwing tantrums when she went off to work. Heather and Blue had become so close, she joked, that they were acting alike. So Heather shut Blue in the kitchen with a toddler gate, removing countertop food and garbage. Things calmed down. Heather began to relax and gave Blue the run of the house again.

Heather, a friend of a friend, had called me for counsel as well. But since she, her vet, her trainer, and her mother had all reached the same conclusion, and since the rampaging had stopped, I didn't give the situation much thought. A month later, though, Heather was back on the phone: Blue had relapsed. She yowled piteously when confined to the kitchen or basement. Worse, she was showing signs of aggression with people and other dogs and refusing to obey even simple commands that were once routine. On one late-night walk, Blue attacked a terrier walking nearby, opening wounds that needed stitches.

Blue's problems had grown so serious that kennels wouldn't board the dog and the vet wouldn't examine her without a muzzle. Heather was thinking of finding her another home, turning her over to a rescue group, possibly even euthanizing her. "She's out of control," Heather complained, exhausted, angry, and frightened. She sounded betrayed—a dog she'd loved and cared for was turning on her because she went to work. "I caused this by leaving her," Heather confessed, guiltily. But was she supposed to quit her job to stay home with her dog?

This time, Heather got my full attention. I took notes, asked questions, then called a canine behaviorist at Cornell and explained the problem in as much detail as I could. "Everybody says the dog was reacting to her going back to work," I suggested. "Everybody is probably wrong," was his blunt comeback. "It's 'theory of mind.' This is what often happens when humans assume that dogs think the way we do."

His analysis: "Being angry at the human and behaving punitively—that's not a thought sequence even remotely possible, given a dog's brain. The likely scenario is that the dog is simply frightened." When Heather was home, she was there to explain and enforce the rules. With her gone, the dog literally didn't know how to behave. The dog should have been acclimated to a crate or room and confined more, not less, until she got used to her new independence.

Lots of dogs get nervous when they don't know what's expected of them, and when they get anxious, they can also grow restless. Blue hadn't had to occupy time alone before. Dogs can get unnerved by this. They bark, chew, scratch, destroy. Getting yelled at and punished later doesn't help: The dog probably knows it's doing something wrong, but it has no idea what. Since there's nobody around to correct behaviors when the dog is alone, how could the dog know which behavior is the problem? Which action was wrong?

He made sense to me. Dogs are not aware of time, even as a concept, so Blue couldn't know whether she was being left for five minutes or five hours, or how that compared to being left for a movie two weeks earlier. Since she had no conscious notion that Heather's work life had changed, how could she get angry, let alone plot vengeance? The dog was alone more and had more time to fill. The damage was increasing, most likely, because Blue had more time to get into mischief and more opportunities to react to stimulus without correction—not because she was responding to different emotions.

I was familiar with the "theory of mind" notion the behaviorist was referring to. Psychologist David Premack of the University of Pennsylvania talks about it; it's also discussed in Stanley Coren's How Dogs Think. The phrase refers to a belief each of us has about the way others think. Simply, it says that since we are aware and self-conscious, we think others—humans and animals—are, too. There is, of course, enormous difference of opinion about whether this is true.

When I used to leave my border collie Orson alone in the house, uncrated, he learned to open the refrigerator with his nose, remove certain food items, open the plastic container, and consume its contents. Then he'd squirrel away the empty packages. Everyone I told this story made the same assumptions: Orson was a wily devil taunting me for leaving him alone. We actually installed a child lock on the refrigerator door. But what changed his behavior was that I began to crate him when I went out. He has not raided the fridge since. Yet he could easily sneak in and do that while he's uncrated and I'm occupied outdoors or elsewhere in the house. Is he no longer wily? Or is he simply less anxious?

There's no convincing evidence I'm aware of, from any reputable behaviorist or psychologist, that suggests dogs can replicate human thought processes: use language, think in narrative and sequential terms, understand human minds, or share humans' range of emotions. Yet that remains a powerful, pervasive view of dogs, the reason Heather's vet, trainer, and mother all agreed on Blue's motivations. It's almost impossible not to lapse into theory-of-mind reasoning when it comes to our dogs. After all, most of us have no other way in which to grasp another creature's behavior. How can one even begin to imagine what's going on inside a dog's head?

Most of the time, I don't know why my dogs do what they do. They seem aware that I have a way of doing things. They've learned that we don't walk in the street, that I don't distribute food from my plate, that there will be a bone or treat after dinner. But they are creatures of habit and instinct, especially when it comes to food, work, and attention. I often think of them as stuff-pots wedded to ritual, resistant and nervous about change.

I don't believe that dogs act out of spite or that they can plot retribution, though countless dog owners swear otherwise. To punish or deceive requires the perpetrator to understand that his victim or object has a particular point of view and to consciously work to manipulate or thwart it. That requires mental processes dogs don't have. The more I've moved away from interpreting my dogs' behavior as nearly human, the easier it is to train them, and the less guilt and anxiety I feel.

To attribute complex thoughts and plots to their actions unravels the training process. Training and living with a dog requires a different theory: that these are primal, predatory animals driven by instinct. Rather than seeking animalclues to her dog's behavior, Heather imagined herself as the dog. She reasoned that if she, Heather, were suddenly left alone for long periods, abandoned by someone she loved and used to spend a lot of time with, she would feel angry and hurt and might try to get even, not only to punish her companion but to try to persuade him or her to return.

That's attributing a lot of intellectual activity to an animal that can recognize a few dozen words but has none of its own, that reads human emotions but doesn't experience the same ones. Since the Cornell behaviorist made sense to me, I conveyed his analysis: The dog didn't know how to behave with Heather gone. Crating Blue would reduce her anxiety and give her less chance to act up. I persuaded Heather—by now distraught—to buy a large crate. For weeks, she fed the dog in the crate, leaving the door open. Between meals, she left treats and bones inside.

The first time Heather closed the crate door, Blue threw herself against the metal, whining and howling. The same thing happened the second, third, fifth, and dozenth times. But Heather, cautioned that training and retraining often takes weeks and months, persisted. Sometimes she left the treat-filled crate open; other times she closed it.

After several weeks, Blue began to go into the crate willingly and remained there quietly for short, then lengthening periods. Heather walked Blue two or three times daily; when she was gone for more than three or four hours, she hired a dog walker to take her out an additional time and throw a ball. But whenever Heather left the house, she put Blue in the crate and left a nearby radio tuned to a talk network.

This time, Heather got it right, treating Blue as a dog, not a rebellious teenager. Blue improved dramatically, and the improvement continues. Her aggression diminished, then seemed to vanish, although Heather no longer lets her near dogs or children unleashed. It seemed the dog had comprehensible rules to follow, and felt safer.

Blue was liberated from the confusion, anxiety, and responsibility of figuring out what to do with her unsupervised and sudden freedom. Once again there was little tension between the two of them. Heather's house wasn't getting chewed up, and homecomings weren't tense and angry experiences. Yet here was a case, I thought, where seeing canine behavior in human terms nearly cost an animal its life.

Sometimes it does. Harry, a social worker in Los Angeles, wrote me that he had a great rescue dog named Rocket and was happy enough with the experience to adopt a second. Rocket attacked the new dog while Harry was feeding them, then bit a neighborhood kid. "He never forgave me for getting the new dog," Harry explained. "He was so angry with me. I couldn't trust him not to take out his rage on others, so I had him put to sleep."

We will never know, of course, what Rocket could or could not forgive. Rocket probably didn't attack the new dog out of anger at Harry. He was more likely protecting his food or pack position. The creature in the household with the most to lose from a new arrival, he probably simply fought for what he had. Then, once aroused, he was more dangerous. As trainers know, dogs under pressure have two options: fight or flight. Rocket decided to fight and paid for it with his life. Had his owner known more about dogs' true nature, he might have introduced the new dog more gradually, or not at all. And there might be one less bitten child. But this is all a guess. We will never know.

When I face such training problems—and I do, we all do—I try to adopt a Sherlock Holmesian strategy, using logic and determination. We have all sorts of tools at our disposal that dogs don't have. We control every aspect of their lives, from food to shelter to play, so we ought to be able to figure out what's driving the dog and come up with an individually tailored approach that works—and if it doesn't, come up with another one.

Why will Clementine come instantly if she's looking at me, but not if she's sniffing deer droppings? Is it because she's being stubborn or, as many people tell me, going through "adolescence"? Or because, when following her keen predatory instincts, she simply doesn't hear me? Should my response be to tug at her leash or yell? Maybe I should be sure we've established eye contact before I give her a command, or better yet, offer a liver treat as an alternative to whatever's distracting her. But how do I establish eye contact when her nose is buried? Can I cluck or bark? Use a whistle or hoot like an owl?

I've found that coughing, of all things, fascinates her, catches her attention, and makes her head swivel, after which she responds. If you walk with us, you will hear me clearing my throat repeatedly. What can I say? It works. She looks at me, comes to me, gets rewarded.

The reality is, we don't know that much about what dogs think, because they can't tell us. Behaviorists tend to believe that dogs "think" in their own way—in sensory images involving their finely honed instincts. They're not capable of deviousness or spite. They love routine: Nothing seems to make them more comfortable than doing the same thing at the same time in the familiar way, day after day: We snack here, we poop there, we play over here. I am astonished at how little it takes to please them, how simple their lives can be if we don't complicate them.

Dogs' emotional makeup (and their ability to express emotions), their pack instincts to follow and obey, and their intelligence are clearly extremely favorable adaptive traits, since they've allowed Canis lupus familiaris, through its partnership with Homo sapiens, to reach population levels that would have been impossible for it in the wild (compare domestic dog populations with wolf populations.)

What's not so often noticed is that man has corresponding traits that allow him to form a partnership with dogs. His own intelligence and emotions clearly enter into it, but so does his instinctive anthropomorphism (which extends to a great many things, not just animals). We can collaborate with dogs so well, and enjoy them so much, because we cannot help but thinking of them as like ourselves. I couldn't agree more with Katz--I've thought many of the things he says for many years--but that doesn't prevent me from thinking and talking about my dogs exactly like they were my children, my friends, my hunting buddies, etc. Like all dog owners, I feel I can read their minds, but in fact I'm attributing to them thoughts they cannot possibly have.

By fortunate accident, dogs' physiognomy and behavior are close enough to ours that we effortlessly substitute our thoughts for theirs. Yet, inaccurate as this must, it obviously works most of the time. I don't see how we could ever have partnered with dogs but for the closeness of the relationship, and that closeness is partly a consequence of our wildly inaccurate anthropomorphizing.

Separation Anxiety Recommendations

These are tips to help dogs who are having separation anxiety issues.

Thanks to Traci Shreyer, MA, for several of the tips below. 614-370-4534

Having a calm, older dog has a relaxing effect for dogs with separation anxiety.

Crate them together or next to each other. Having one dog loose and one free roam will likely upset the dog with sep anxiety.

Use a fan, bubble machine or something that can provide white noise to lull/calm the dog into sleep. Radio/Television are not as effective and

sometimes have the reverse effect because of changes in pitch/volume/site.

A daily walk will provide physical and mental stimulation.

Daily exercise. Hard running is best or swimming, biking, jogging, dog play, roller blading. You can get the Springer bicycle jogger from

Foster & Smith’s 1-800-826-7206.

Day care can be a good exercise opportunity during the early parts of treatment for separation anxiety.

Remember, a tired dog is a good dog.

Thanks to Traci Shreyer, MA, for several of the tips below. 614-370-4534

Having a calm, older dog has a relaxing effect for dogs with separation anxiety.

Crate them together or next to each other. Having one dog loose and one free roam will likely upset the dog with sep anxiety.

Use a fan, bubble machine or something that can provide white noise to lull/calm the dog into sleep. Radio/Television are not as effective and

sometimes have the reverse effect because of changes in pitch/volume/site.

A daily walk will provide physical and mental stimulation.

Daily exercise. Hard running is best or swimming, biking, jogging, dog play, roller blading. You can get the Springer bicycle jogger from

Foster & Smith’s 1-800-826-7206.

Day care can be a good exercise opportunity during the early parts of treatment for separation anxiety.

Remember, a tired dog is a good dog.

- Sit for everything- this means he/she should sit before they get to do anything good (be fed, get a treat, fetch, be let out, petting) They don’t have to stay. It is like saying, ”Please”.

- Daily obedience. Just a few minutes each day, make it fun, use the clicker. This will help build confidence, & be exposed to a positive noise.

- No punishment. This is particularly the case for anything that you did not see happen. This will just add stress

- Don’t increase his/her fear with soft, quiet petting & talking. Ignore him/her until they do something brave or act like it’s no big deal & “jolly her up”. Especially during storms!

- Group clicker class. Dog Talk (614)792-6331. Positive obedience classes can be very confidence building.

- Create storm parties. Play, do commands for treats, offer a stuffed enrichment toy. This will help teach good things can happen during a storm.

- Offer enrichment toys when you leave. They should be stuffed with great food. Sometimes offer them while you are home so you can be sure they like what you are offering, & so they won’t associate them with stress. Good options are: the Kong, Buster Cube or treat ball, Havaball, Planet pet goodie ship, & sterilized bones.

- Special time. This should be at the same time, place, person, private- the best five minutes of their day.

- Take him/her out to get the mail with you. A small walk for you, but a reward and adventure and confidence builder for the pooch.

- Desensitize him/her to your leaving cues (ex. shoes, coats, keys, garage door). Present the cue, ask for a sit, click & treat, then remove the cue & go about your day.

- Keep your reunions & departures low key. Ignore him/her for about the last 15 minutes before you leave & the first 15 minutes you are home (or until he/she is no longer seeking attention from you. Let her out to eliminate if necessary. Do not plan any “fun activities” like walks, play, or meals for the first ½ hour you are home.

- Consider trying DAP (dog appeasing pheromone). This is a new product that your veterinarian can order through Butler .